By Josh Metten – Jackson Hole EcoTour Adventures

Twice a year a stunning transformation sweeps over the landscape surrounding Yellowstone National Park. Great herds of animals migrate to more sheltered valleys for winter and return in spring, following a wave of greening vegetation into the mountains. This ancient strategy has enabled them to thrive.

By migrating, animals can find protection from severe winter weather and access the best quality forage as it emerges across the landscape in spring, an ancient strategy which has enabled them to thrive across the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. But many of these migrations may be at risk, and without help could be lost forever.

6000 years of Pronghorn Migrations

Travel across the windswept “sagebrush sea” of Idaho, Wyoming, or other states in the western U.S. and you will inevitably spot North America’s fastest land animal, the Pronghorn. Each spring, herds of pregnant does, led by a dominant matriarch, follow ancient migration routes to summer range, including the now protected 100 mile long “Path of the Pronghorn.” The route takes them from critical winter range near Pinedale, Wyoming into the Jackson Hole Valley.

Many will cross specially designed overpasses along HWY 89/191 at Trappers Point, guided to the structures by fences which keep them off the road. Underpasses, preferred by other animals like mule deer, complete the wildlife corridor. And it is working. Since the completion of construction, the area has seen a decline in wildlife-vehicle collisions by close to 80%, a win for wildlife and humans alike.

Marathon Migrations: Mule Deer go the Distance Across Wyoming and into Idaho!

For years, the “Path of the Pronghorn” has been touted as one of the longest migrations in the Americas, second only to a caribou migration in the Arctic. But Wyoming, and the wild country of the western United States hold more spectacular migrations, hidden in plain view.

Rewind back to summer of 2016 in Grand Teton National Park. I watch a mule deer doe cross the road near Jackson Lake, heading north. Where did she come from? Perhaps she wintered on the buttes above Jackson, traveling only a short distance. Or maybe she spent the winter to the northwest, on private ranchland across the Teton Range in Idaho. Deer Collared by GTNP biologists have done both.

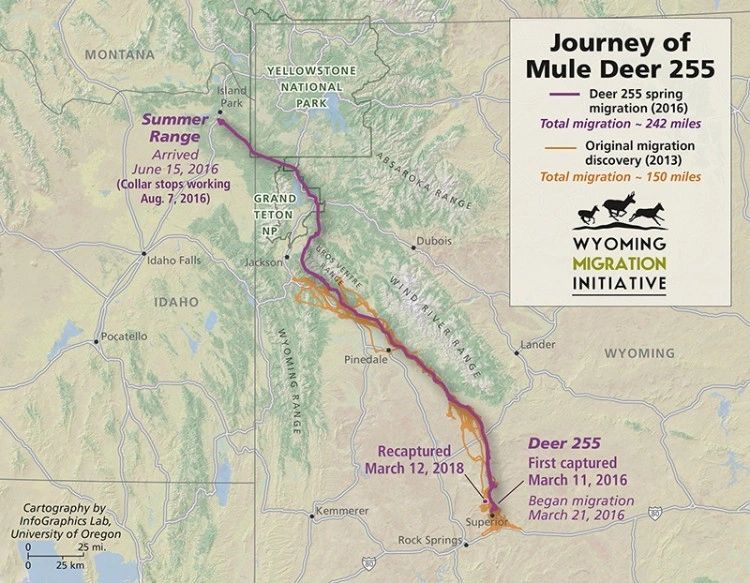

I like to think she is a relative and fellow ultra marathoner of 255, a doe collared by the Wyoming Migration Initiative in spring of 2016. 255 belongs to a herd of deer who migrate along the Red Desert to Hoback migration route, a recently discovered 150 mile long route which crosses the state.

But 255 took the migration a big leap further, all the way to Idaho. She continued north, leaving other members of the herd behind, climbing over the Gros Ventre Mountains and dropping into Northern Grand Teton. After walking the entire length of Jackson Lake 255 crossed at its northern end leaving the park and settling down for the summer in Island Park, Idaho.

In the end she had traveled close to 250 miles, an incredible distance. But would she return in the fall or was this movement just a fluke? Biologists would have to wait, as her collar failed and she disappeared for two years.

For wildlife biologists in Wyoming, March represents a flurry of activity, as crews travel across the state capturing and collaring animals to study their migrations. Using helicopters, deer are netted and brought to waiting biologists who quickly take measurements and fit the deer with new collars to track their movements before releasing them unharmed. One of the deer carried with it an old, non functioning collar. After two years, 255 had been found, alive and well.

The return of 255 to the Red Desert confirms the success of what is now the longest mule deer migration in America. Ultra Migrations like this one make us rethink what it means to be a mule deer in the west. These tenacious animals are willing to go the distance to maximize their chances of survival, whether navigating hundreds of fences, avoiding cars while crossing busy highways, or squeezing through small pinch points adjacent developments.

Protecting Migration Routes

Excitement over these migrations has gone federal. In February, Interior Secretary Brian Zinke directed the Department of the Interior to prioritize working with local agencies to protect migrations on federal lands. Working with local ranchers to modify barb wire fences, like the ones the RDH mule deer must cross for easier passage, was one of several local solutions referred to in the release.

We’re thrilled to see the DOI supporting the conservation of migrations, a much needed step in the right direction. Though corridors like the Path of the Pronghorn and RDH mule deer migration are being conserved there is much more to be done across the west.

Preserving America’s Last Great Migrations

Last summer, I rode my mountain bike 30 miles through the Lionhead Mountains north of Island Park, taking in the stunning vistas, alpine lakes, and wildflower meadows. It’s easy to see why this place is special to so many, it’s become a part of who we are, our culture. Places like the Lionhead, Targhee Pass, and Island Park are also habitat for thousands of migratory animals, each following routes that have been passed down from generation to generation.

This ancient knowledge, this culture, is not only what makes the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem so special, but is central to its existence. As “the lifeblood of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem” to quote biologist Arthur Middleton, migrations quite literally move nutrients across the landscape. They fertilize the soils and sustain our apex predators including mountain lions, grizzly bears, and wolves. The predators in turn feed scavengers, such as bald and golden eagles, foxes, coyotes, and even small songbirds.

Migrations are also intertwined in western culture; hunting in Idaho alone accounts for around $500 million in economic activity.

But most importantly, they connect us across the landscape and are a reminder of our wild past. May they forever persist into the future.

Born and raised beneath the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, Josh Metten is a Professional Naturalist with Jackson Hole EcoTour Adventures. In his free time he enjoys hunting, fly-fishing, mountain biking, rafting, skiing, and exploring the the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Join Josh on a half day, full day, or multi day wildlife safari in Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks here: www.jhecotouradventures.com@jacksonholecotours @joshmettenphoto