By Mike Koshmrl Jackson Hole Daily January 15, 2020

Every time a multimillion-dollar wildlife overpass or underpass is proposed to ease vehicle-wildlife collisions, one stakeholder or another suggests enacting a speed-limit reduction instead.

It’s an understandable, intuitive reaction. Who wouldn’t want to spend less money on a solution that could be implemented much more easily? The problem is, lower speed limits, especially on two-lane rural highways, don’t work.

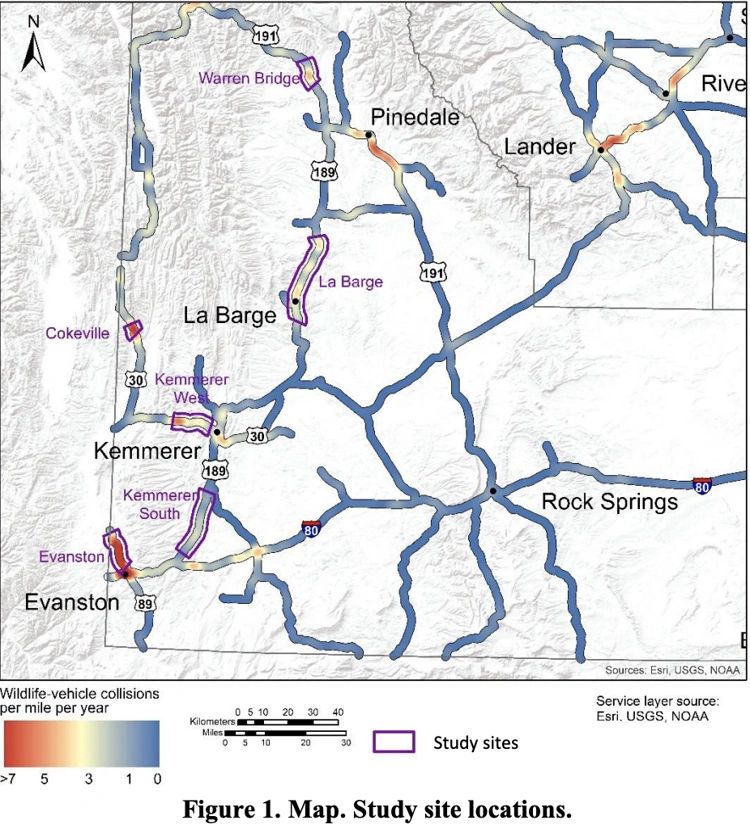

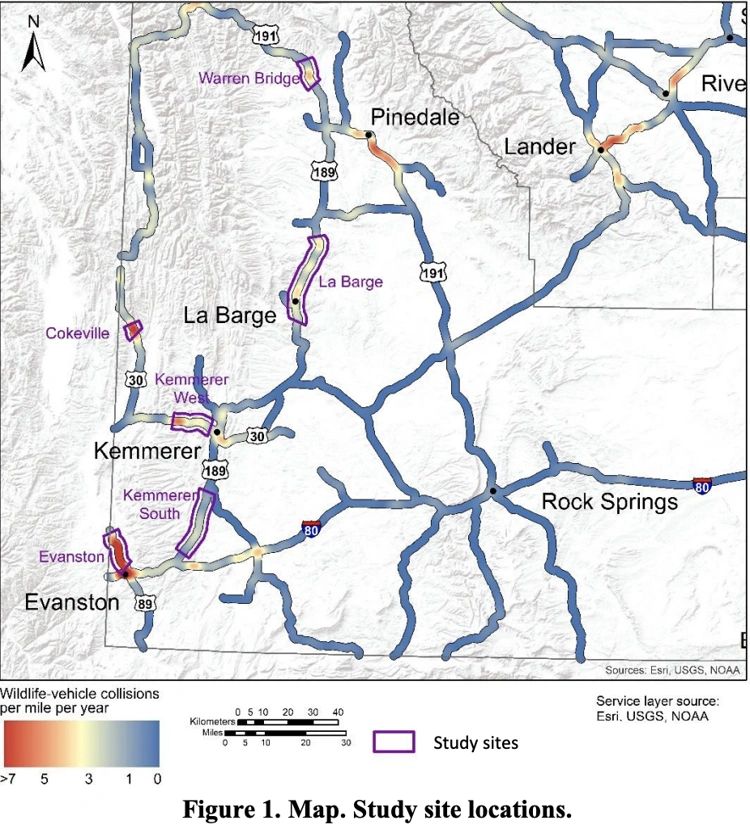

That’s the conclusion The Nature Conservancy and Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative recently reached after assessing years worth of data from experimental 15 mph nighttime speed-limit reductions on six stretches of highway in southwest Wyoming.

“From the data that we looked at, we didn’t find any difference in the number of collisions that were occurring between the reduced and normal speed limit areas,” Nature Conservancy scientist Corinna Riginos told the Jackson Hole Daily. “In both cases, it was because drivers were still going quite fast. Even though they slowed down a little bit, they’re still going pretty fast, and it makes good sense that at that speed — around 65 mph — drivers and animals just don’t really have enough time to avoid each other.”

Riginos, a former Jackson resident, led the research, which the Wyoming Department of Transportation funded.

Although WYDOT slashed nighttime speed limits from 70 to 55 mph at the test sites, motorists on average slowed down only 3 to 5 mph. The disregard for the posted maximum speed held true across all six study sites, three of which were selected because they bisected mule deer migration routes, and three because they overlaid mule deer winter range.

At the three winter range sites, 237 carcasses accumulated. There were no fewer collisions on the test stretches — in fact, Riginos said, there were slightly more.

Riginos similarly found no statistically significant differences in how deer interacted on the highways during periods of reduced speed limits. Traffic volume was the one variable that made a difference.

“The higher the number of cars going by,” Riginos said, “the more likely they were to have near misses and the more attempts to get across the road the deer had to make.”

The results were unfortunate for wildlife managers and highway departments that have sought less costly and infrastructure-heavy means to drive down roadkill rates. Signage, speed-limit reductions, animal-detection systems and other collision deterrents have all been pitched as solutions, but when it comes down to it, crossing structures such as overpasses and underpasses — which are more than 80% effective — are the only proven fix, Riginos said.

“We can keep trying to layer on these things that will hopefully make some difference to human behavior,” she said, “but there is a bit of a leap of faith whether we’re actually going to change behavior.

“It continues to be incredibly tempting to think that we’re going to find an easy fix to this problem — and I would love for that to happen — but unfortunately we just keep finding that crossing structures are the best thing, and nothing else really comes close,” she said.

In Wyoming, wildlife-vehicle collisions run up a societal tab of more than $50 million annually, factoring in expenses related to human injury, property damage and the loss of wildlife.

Riginos emphasized that the lack of compliance torpedoed the effectiveness of lower nighttime speed limits, but roadkill rates and speed are well correlated by recent research: There were 61% more deer-vehicle collisions in places with round-the-clock speed limits of 65 mph compared with 55 mph.

The roads studied were as near as Highway 191 at Warren Bridge and as distant as Highway 89 near Evanston. The data collection period spanned from fall 2016 to spring 2018.

A copy of the report summarizing the research is attached to the online version of this story at JHNewsAndGuide.com.